Nigeria’s Power Generation Disaster

Everyone born and raised in Nigeria under 45 has never witnessed an uninterrupted power supply regime, and they do not expect otherwise. The latter is the heartbreaking reality of the magnitude of the crisis. Those who have governed Nigeria for the past five decades should not be involved in Nigerian decision-making. This article will examine the failure, missed opportunities, and potential solutions.

Failures:

Nigeria’s electricity generation from forty years ago remains almost unchanged despite a practically triple increase in population. In other words, a family of four (father, wife, and two children) has four lunch plates daily. The wife is pregnant for number three, but there is no plan to create room for a fifth plate. Such a family is bound to have a reduced lunch portion. In Nigeria, the family grew to eight, forcing them to ration, increasing hunger and hardship. That is what has happened to Nigeria.

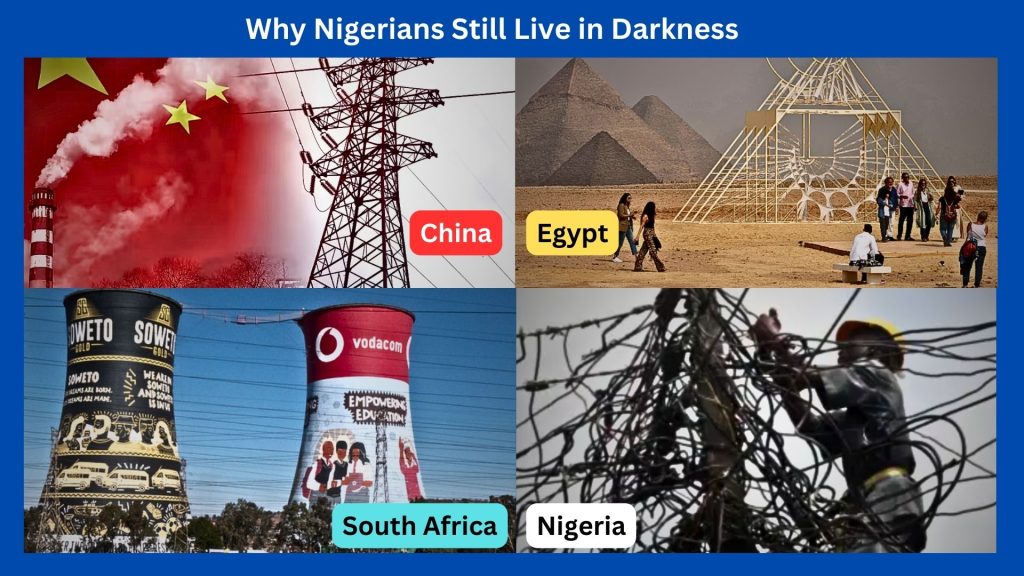

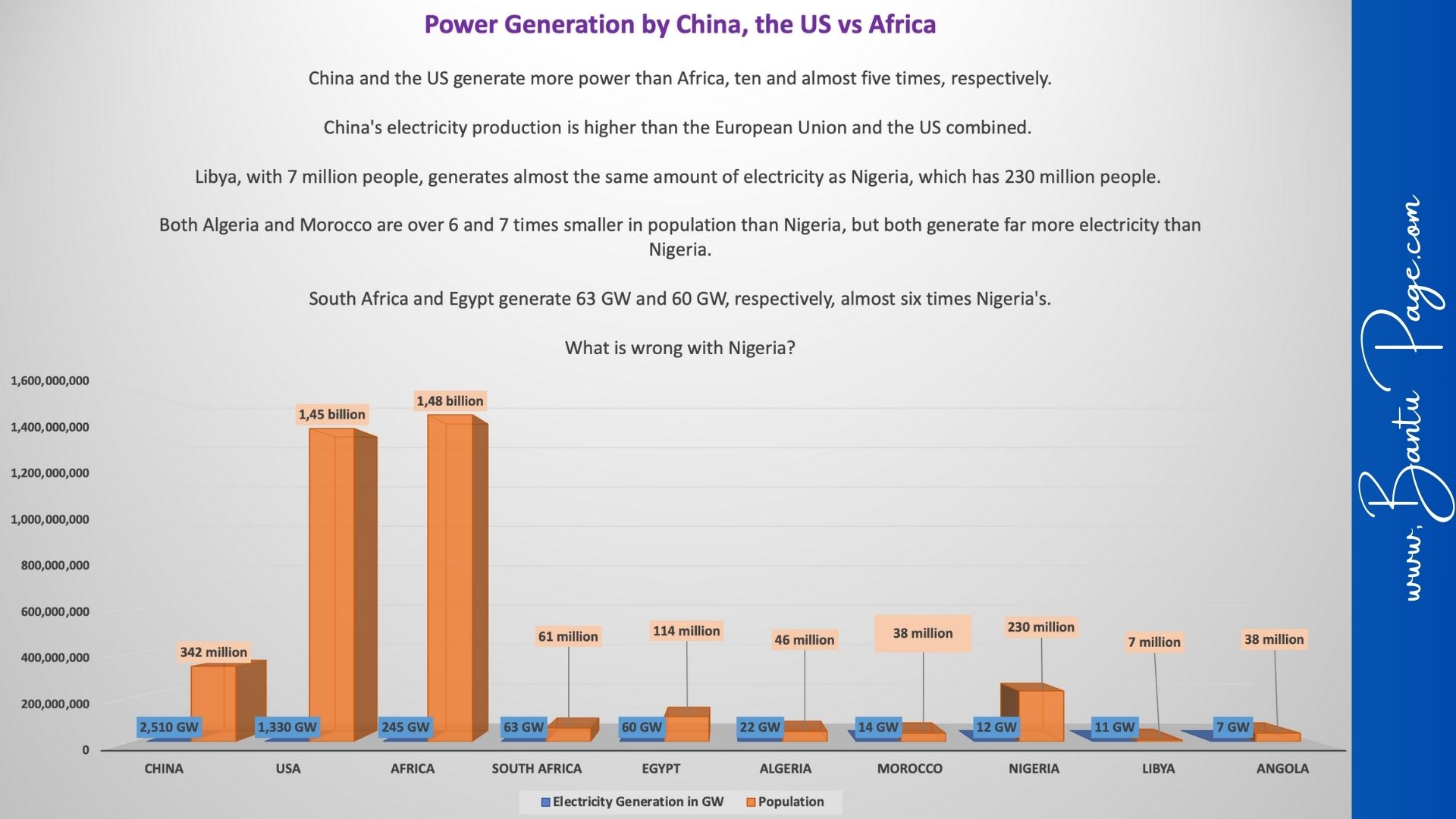

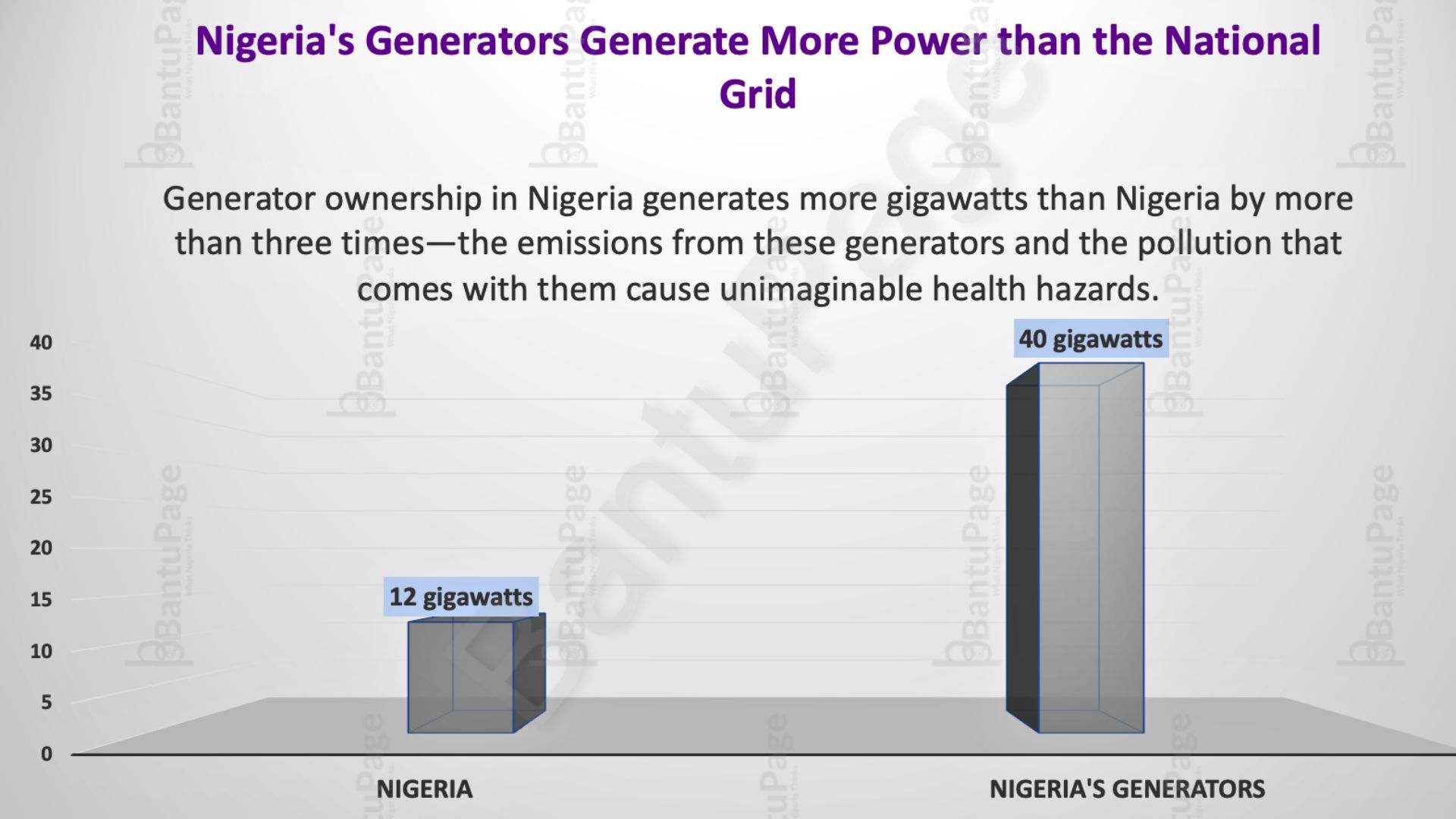

With 230 million people, Nigeria generates barely 12 gigawatts, compared to South Africa and Egypt’s 61 million and 114 million people, respectively, generating 63 and 60 gigawatts. With 7 million people, Tiny Libya generates 11 gigawatts, almost the same as Nigeria. Algeria, 46 million people, and Morocco, 38 million people, also generate more than Nigeria, at 22 and 14 gigawatts, respectively. The situation in Nigeria is so severe. Generators have become part of the Nigerian structural master plan. In some areas, the noise pollution from generators is deafening. Estimates infer that over 100 million Nigerians go to bed without power daily.

Almost every public and private institution in Nigeria reflects this reality. The failure is fantastic. As we speak, the domino effect of that failure is doubling at an unprecedented speed. Despite this, the free fall continues unabated. Nigeria privatised its power generation a while ago, and like all private companies, profit is the driving force. The price of electricity has increased threefold, but its reliability is low. In the last decade alone, the funds allocated to politicians’ welfare could have facilitated the construction of four new power stations, thereby bolstering the deteriorating grid that has undermined industrial and private productivity. Nigeria is not a normal country.

Missed Opportunities:

The successive administrations that have come and gone have all missed the opportunity to embark on fundamental changes to the power sector. The egg has gone so bad that load shedding, which sometimes grapples up to 60% of Nigeria into darkness for days, has become so routine that Nigerians no longer complain. On the contrary, Nigerians are surprised when they receive an uninterrupted power supply for a six-hour sequence. Power is the backbone of every country’s development in the 21st century. Uninterrupted power supply is at the core of industries, FDI, education, and productivity in general. The situation has deteriorated so bad that private generators produce more gigawatts than the national grid.

Why would those in charge of Nigeria’s affairs let the country deteriorate so badly? Do they have an ounce of shame? When will this end? The annual cost of fueling the country’s endless generators could construct a geometric power plant capable of sustaining entire states. Successive Nigerian governments have taken countless loans for initiatives that have only served to enrich themselves. Why didn’t these loans address the fundamental issue at hand?

Potential Solutions:

The Three Gorges Dam in China generates 22.5 gigawatts, 10 gigawatts more than Nigeria’s total electricity generation. The Aba geometric power plant generates 188 megawatts—a project that cost just $800,000. Over the last ten years, the maintenance cost for our three moribund refineries exceeded $25 billion. That could have given us 28 geometric power plants, i.e., 5 additional gigawatts towards the national grid. Fuel and other subsidies and the consumption-addictive policies financed from oil revenues without productivity have amounted to over $300 billion in the last forty years. They could have given Nigeria over 150 gigawatts of power generation.

Fair enough, we are looking for solutions, not complaints. “Those who do not learn from history are bound to repeat it.” Now that we are aware of the waste of Nigeria’s money, what steps are we taking to prevent further wastage? Unfortunately, the answer is not encouraging! A ruined country should have a plan, like a restaurant’s menu. Nigerians are resilient. They can bear hardship like no other country in the world. Nigerians would accept hardship under a concrete plan. A five-, ten-, or even fifteen-year solid plan would see sacrifices from Nigerians as long as a new Nigeria is born; the people would accept and understand, provided such a plan is fully implemented with the unrelenting effort put in place to tackle the unacceptable injustice Nigerians face every day.

Most subsidies have now been removed. Soon, a year would have passed since that clumsy decision on President Tinubu’s inaugural day. What has happened to the fuel subsidies? How much was the subsidy? How much was saved? What do we intend to do with the savings? When a company’s revenue drops significantly, shareholders, directors, and those at the helm reduce their benefits and remuneration to reflect the underperformance. Nigeria’s revenue has boldly dropped. It has created more poor people in the last 24 months alone than in the previous 20 years on average, yet its legislators and those at the top have not suffered an ounce of slash to their exorbitant remunerations. How can you expect such people to impact the change that Nigeria requires?

Conclusion

Over 70% of Nigerians are under 35, and less than 3% are over 65. Yes, you heard me. Most Nigerians do not read or involve themselves in the country’s affairs. They have established nations within the country, prioritising ethnic identity over national unity. Of that 70% under 35, a staggering 60% are under 25. They have a different view of the world. Their worldview focuses on Western pronouncements. They have forsaken their domestic struggles in favour of a foreign identity. With such a mindset, those in power in Nigeria benefit from an almost zero challenge to their rule by a majority whose interests lie overseas. The average age of the Nigerian legislator is 50, whereas the Nigerian average age is 18—generations apart.

A country must become a nation to fight together, and a people must become a nation to achieve the same goal. For a country to become a nation, it must share the same ideals and worldview—Nigeria does not have nationhood characteristics. It has disunited people whose goals are incompatible with the Nigerian dream. I fear that Nigeria may not improve until we resolve this issue.

By Ikechukwu ORJI